San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) – San Francisco

September 14, 2018

The Getty Villa – Pacific Palisades

March 5, 2019Hail Hale!

Mount Wilson Observatory – Mount Wilson

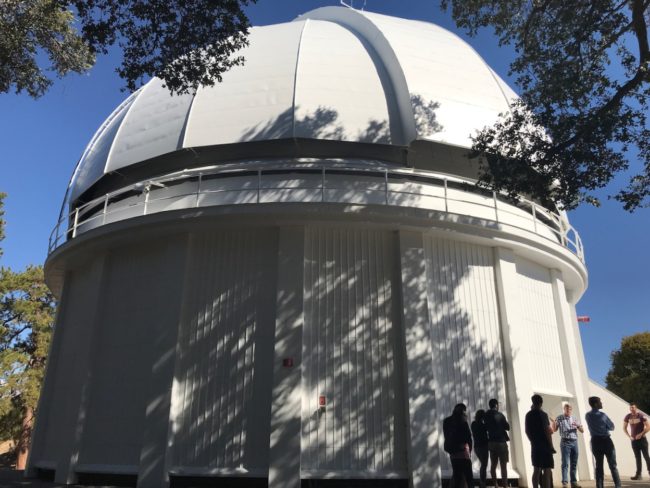

Tracy and I had talked about visiting the Mt. Wilson Observatory on numerous occasions. However, we wanted to wait for a clear day to make the trek up Angeles Crest Highway in the San Gabriel Mountains to see it. This being Los Angeles, we had to wait for a while.

That day recently arrived, so we hopped in the car and, dodging speeding motorcycles, bicycles and vehicles at every turn along the way, survived the 45-minute drive from Pasadena to this famed astronomical landmark located at an elevation exceeding 5,000 feet. Although not as clear as we had hoped, the views of the Los Angeles basin weren’t too bad on the drive.

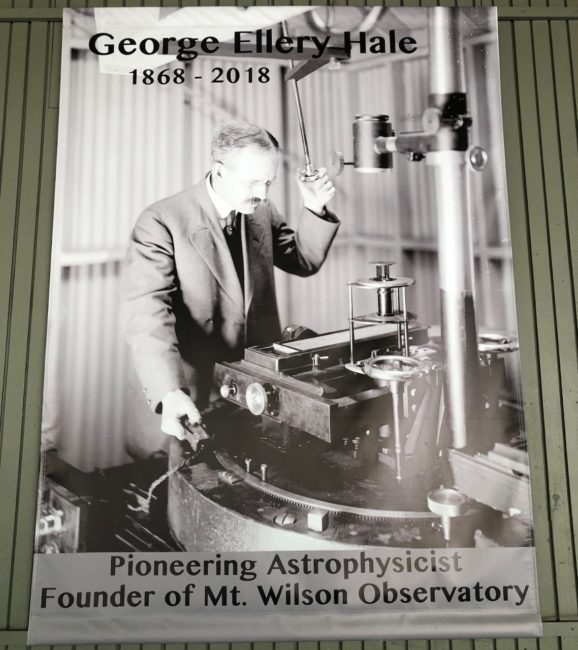

When we arrived at Mount Wilson, the weather was pristine and perfect. Pioneering astrophysicist George Ellery Hale founded the observatory in 1904.

On weekends, there is a two hour (or longer) guided tour, and we arrived about 30 minutes early, purchasing our tickets at the Cosmic Cafe. For the last 20 years, Mt. Wilson has been open more to the public with tours and events making it a destination.

For a few moments, we looked around at all the TV and other electrical towers that dot the mountainside.

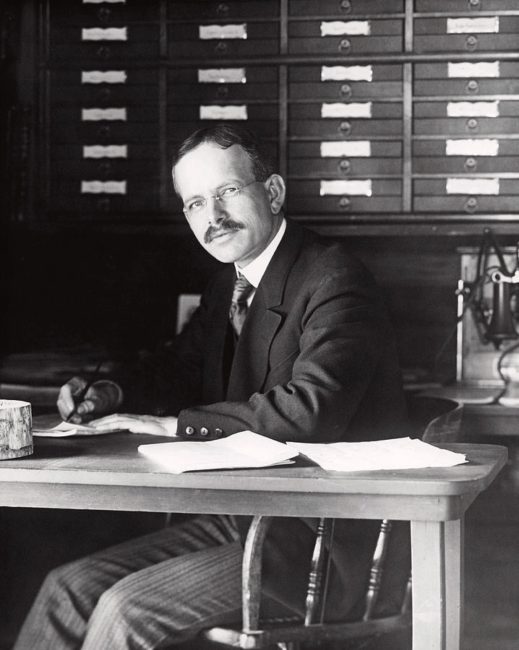

Our tour commenced promptly at 1 p.m., and our docent (Michael) might have been the most knowledgable guide we’ve encountered, which is remarkable since he just began doing these tours this past spring. Michael first gave us a little background on Hale, who led quite a life and was very good at persuading prominent people to fund his projects. That gift started when he was young. (Hale has been described as an “extremely industrious and precocious teenager.”) . Historical photos courtesy of Carnegie Institute & Huntington Library

As a child, George Hale convinced his father (who made his fortune in the elevator business), to buy him microscopes and telescopes, but his dad made him write out proposals for why he wanted each device and what he was going to do with it. This fortuitous training helped George became good at convincing rich men to spend money. It also didn’t hurt that the young Hale was also brilliant (he graduated from MIT).

Hale’s first project in 1890 was the installation of the 40-inch refracting telescope at Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin. At that time, it was the largest refractory lens in the world. Problems ensued there, and it was determined that Mount Wilson had the steadiest atmosphere for viewing in the U.S. Hale even climbed trees with lens and binoculars to be sure this was the case. I guess you could say he scoped out the territory.

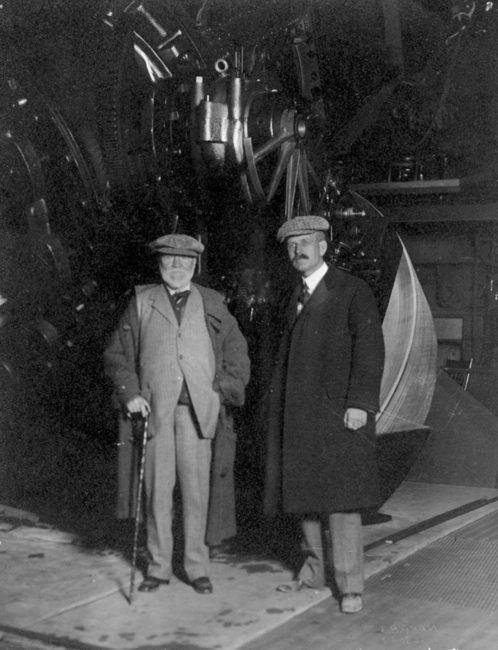

How convincing was Hale in securing the necessary funds? In 1902, Andrew Carnegie (seen below with Hale) established the Carnegie Institution of Washington to support original research in all scientific fields. Hale found out about that, and those written proposals as a kid paid off. The Carnegie Institute owns all the equipment.

Hale founded the observatory in 1904, leasing the land from the owners of the Mount Wilson Hotel under the condition that public access would be allowed. The original lease for the property was $1 for 99 years (the Mt. Wilson Institute runs the observatory). Thus, the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory was born.

All the equipment came up the Mt. Wilson Toll Road on mules and horses, which is remarkable when you realize the road had to be widened to all of four feet (Angeles Crest Highway did not open until 1935). For instance, the dome for the 100” Hooker telescope weighs 500 tons. Fortunately, it came up in separate pieces. (and we thought our drive was dangerous)

For historical context, Michael told our group of 24 that in the 1890s the population of Pasadena was 5,000 people and Los Angeles had only about 50,000 people. Initially, there was a hotel on the site, and people would ride mules up the original 2-foot wide Mt. Wilson Toll Road (no thanks) to the hotel. There was also a railway to nearby Mt. Lowe (below photo courtesy of Metro Transportation Library and Archive), where a popular hotel was located until it was lost to a fire.

The tour began with views of the tops of two of the telescopes (150-foot solar observatory on the left and 60-foot solar observatory on the right) in the distance. It’s a pretty easy walk (a little more than a mile in total, and although it is not flat, the tour is not that strenuous).

We stopped to look at a place where a group of Harvard astronomers took an expedition in the late 1880s and early 1890s to check out the area. Its leader, William Pickering, said, “I consider this the point of all others to place the largest and finest telescope in the world.” Pickering’s brother Edward agreed, however, he felt bringing equipment up those narrow trails would be next to impossible. Never underestimate a mule!

We stopped near the 150-foot Solar Telescope.

Before going inside to check it out, our group visited the nearby Astronomical Museum.

Inside is a plethora of information and photos of Mount Wilson’s telescopes …

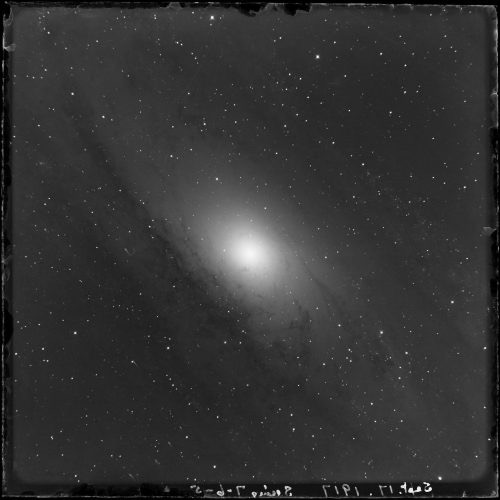

… and visions seen by those telescopes.

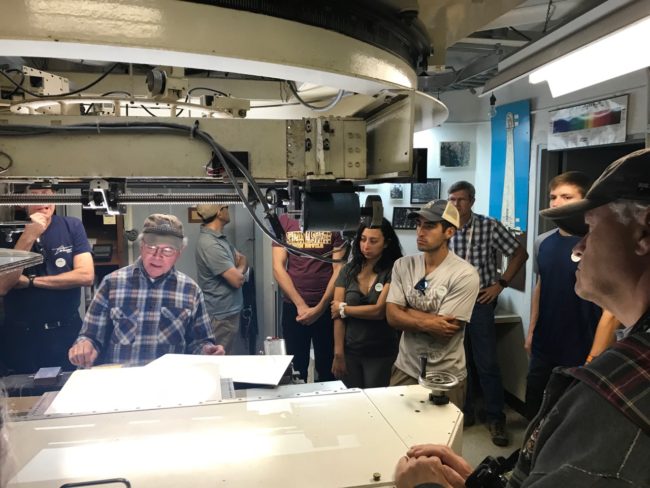

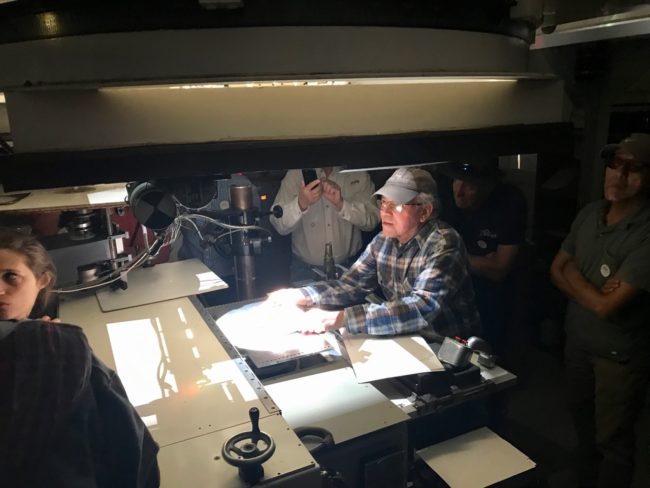

Following that interlude, we walked back to the 150-foot Lunt Solar Telescope, where an astronomer named Steven, who has been here for 40 years, asked if we wanted to hear about sunspots. There were no sunspots to be seen on this day (except for a few on my arms). It’s no longer used for scientific research, although they still track sunspots and flares. It has been monitoring sunspots since 1917. We learned the largest sunspot was seen on April 6, 1947. A large spot was also seen in October 2014, during a partial solar eclipse.

Steven was quite scientific in his talk about sunspots and how the solar telescope functions, and although I did ace my Astronomy final in college (one of the few), I have to admit some of it was over my head. However, this being astronomy, “over my head” was to be expected.

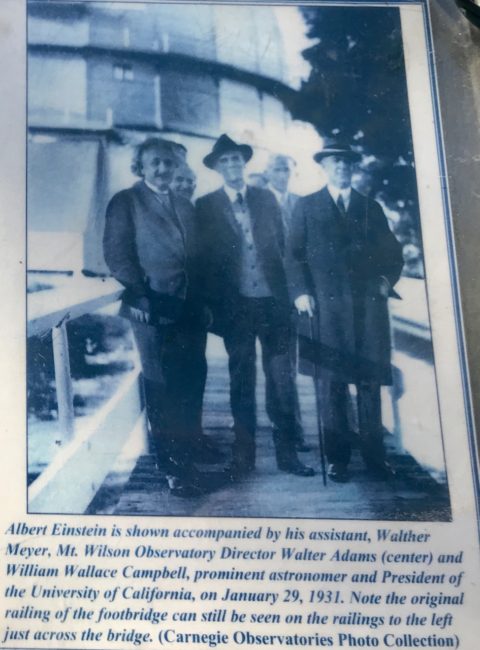

He also showed us the lift that takes him to the top of this telescope. It’s the same lift that took Albert Einstein to the top when he visited in 1931, and it shows its age. Steven admitted television’s Huell Howser was a bit uncomfortable as he rode that bad boy to the top when he featured the observatory on his show. I’d love to ride it. It’s on my “bucket” list.

Stephen Hawking also visited here and signed the guest book with his thumbprint. The guest book with Einstein’s signature was stolen. There’s also a bust of George Hale.

We walked for a short distance to the Snow Telescope Dome, the second of the three telescopes we could visit. There is a short set of stairs to climb. The 60-foot Snow Solar Telescope was installed in1908 using the 40-inch lens from the Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin. From the Mount Wilson website: “The Snow Telescope, the oldest telescope on the mountain, is named after the father of its benefactor, Helen Snow. She donated money for its construction at Yerkes Observatory in Williams Bay, Wisconsin. George Ellery Hale moved the telescope to Mount Wilson in 1904 to make observations of the Sun.” This was the largest operational telescope in the world when it was completed in 1908, and the first night-time telescope on Mount Wilson.

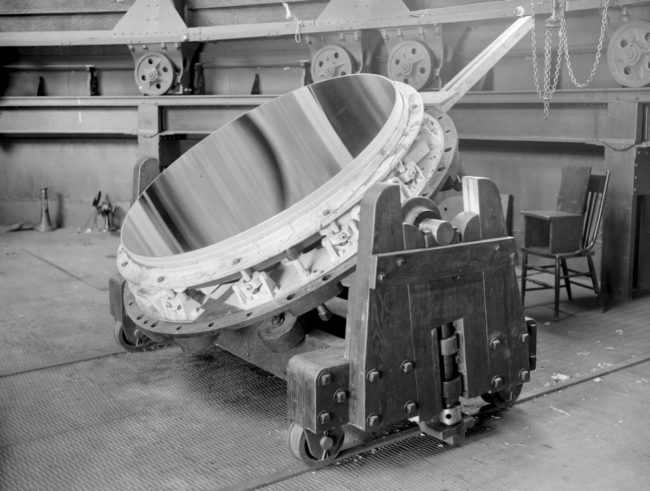

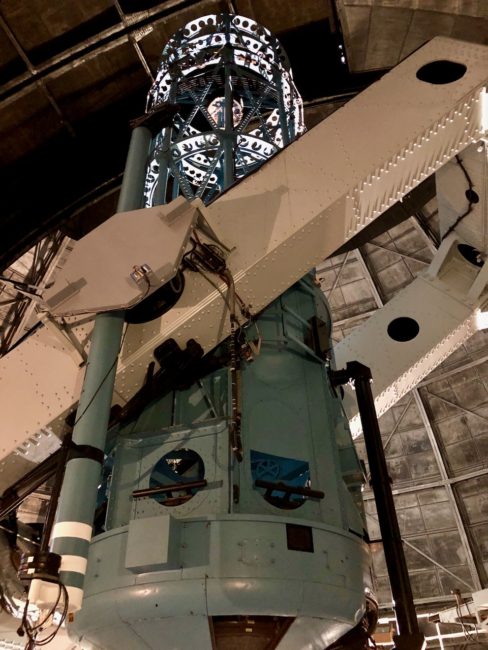

My dedicated scribe (and lovely bride) Tracy took copious notes. The tower housing the 60-inch reflecting telescope was designed by George Ritchie. The lens made in France weighs 1,900 pounds and was a gift from George Hale’s father in 1896.

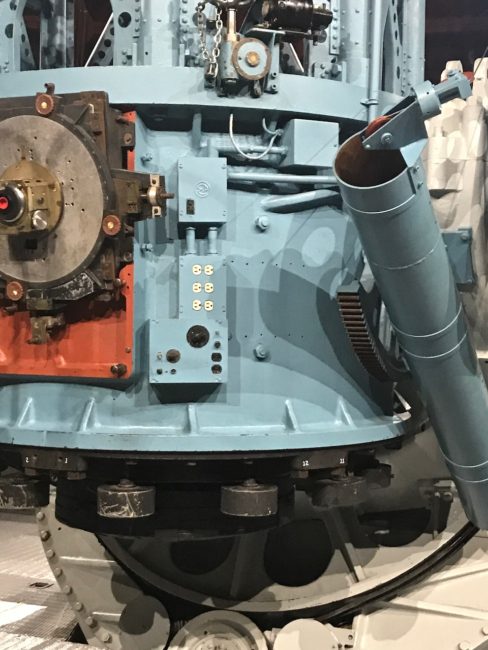

The Carnegie Institute funded the construction of this telescope. The telescope weights 23 tons and floats in 650 pounds of mercury to help it rotate. In all, 700 tons were transported up here for the 60-inch telescope. Chicago’s famed architect D.H. Burnham designed the dome.

The telescope almost never got here. From the Observatory website: “As the mounting was nearing completion, unexpected difficulties caused delays. On April 18, 1906, the great San Francisco earthquake caused considerable damage at the Union Iron Works, but the 60-inch “escaped injury, though by the barest of margins.” However, reconstruction and labor strikes caused the shipment of the mounting to be delayed for many months.”

The telescope was functional in 1908 and was used by Harlow Shapley to measure the size of the Milky Way in 1918. They’ve yet to ascertain the size of a Three Musketeers bar.

Shapley was assisted by female “computers,” especially Henrietta Swan Leavitt who was working for Harvard to catalog the sky by measuring the brightness of the stars. It was very cold in the tower, so after WWII they purchased war surplus stores’ electronically heated bomber flight suits to wear while observing.

They even have an outlet in the telescope where they could plug in the suits.

During the 1933 Long Beach quake the mercury slopped out of its container landing on the 100” lens which was out for cleaning, the mercury ate away the silver on the lens. The mercury container is now enclosed, which is a good thing. By the way, this tower is available to rent out for $1,000 per night for events (Bomber flight suits not included).

As you can see, Michael does not leave any stone unturned in his explanations. He asked people to get down to look at the telescope from this level, but I deferred because I still might be there trying to get up.

The telescope is today the largest telescope in the world made exclusively available for public viewing.

To get to our next destination, we walked across the “Bridge To The Stars.” It seems Hale would not allow his astronomers to eat in the telescope domes, so this footbridge connects the 100-inch telescope dome to the “Galley,” where they could cook up a midnight meal. It’s also the bridge that Einstein walked across (yes, he survived “The Bucket” ride) on January 29, 1931, to see the telescope in person.

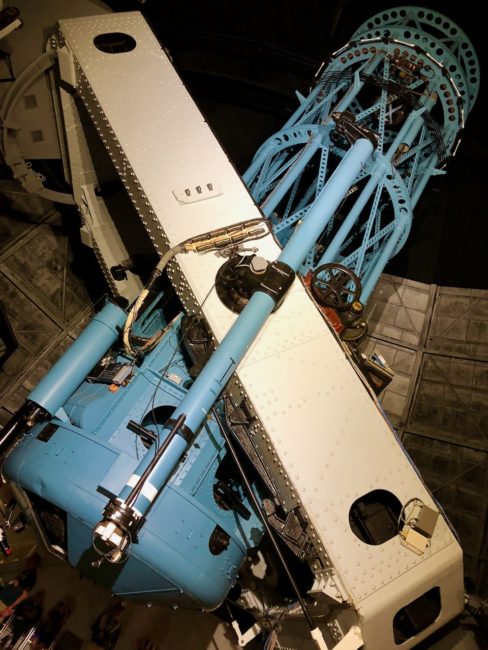

Our final telescope on the tour was the famous 100-inch Hooker Reflecting Telescope, which Edwin Hubble (yep, that Hubble) used to discover the expanding universe. These findings run backward led to the Big Bang Theory and a hit CBS Show (I might be confused again).

John Hooker was an L.A .businessman who Hale convinced to fund $45 thousand for the casting of the 100” lens from France. I told you Hale was good at this.

Numerous attempts were made in France at pouring this lens, but it still had air bubbles trapped inside. Ritchie configured and polished the lens in 1917, and some think the air bubbles actually helped with viewing. The first viewing was a disaster with six images showing. There was some thought that it was distortion from the heat as the roof had been open during the day. Unable to sleep, Hale came back at 3 a.m., and only one image could be seen. Whew!

This telescope weighs 100 tons and was also hauled up by mules and horses. Hubbell joined the staff in 1920 and was the first to discover the Andromeda Galaxy, which he calculated was 900,000 light years away (it is now known that it is 2.5 million light years away). This telescope was used for scientific purposes until 1985 (lights from surrounding cities took its toll on viewing). However, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) has used it in recent years to take a high-speed video of its Juno project.

From 1917 to 1949, this was the largest aperture telescope in the world.

Note: There are two longer staircases to see the Hooker reflecting Telescope, so be aware of that fact.

That did it for one of the most (as Mr. Spock would say) “fascinating” tours we have taken. Michael was an excellent guide, and our group asked some very intelligent questions, and he answered them all in ways even I could understand.

To take the 2+ hour tour; you need to get a day pass for parking ($5 available at the Cosmic Café or Haramokngna Cultural Center). The cost is $13 for seniors and children under 13 and $15 if you have a younger er wife. Private tours are available and so are telescope viewing reservations (see below).

There are also lots of hiking options and picnic tables overlooking the L.A. Basin, plus endless views on a clear day (they do sometimes occur, but don’t count on it). The Cosmic Café is open on Saturday and Sunday from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. for tour tickets and a bite (the apple pie looked good).

The drive back down afforded more great views and, yes …

… trees actually do turn color in Southern California.

For the first half of the 20th century, Mount Wilson was the most famous observatory in the world, and it’s still a cool place to visit. It had taken some time to find the right day to drive up here, but our wait was rewarded with a great tour on a beautiful day in the San Gabriel mountains. Most people who visit Los Angeles (or who even live nearby) tend to visit the Griffith Park Observatory.

As much as we like it, we think the Mount Wilson Observatory is even a more exciting and interesting place to venture. Give it a shot when you’re in the L.A. vicinity.

Mount Wilson Observatory

Mount Wilson, CA

(Hours and Open Days depend on the time of year and weather conditions … check website)

Website: mt.wilson.edu

Private Tours: tours@mtwilson.edu

Telescope Viewing Reservations: mtwilsontelescopes@gmail.com

Parking: Free

.

.

.

.

.

.